Gone with the Wind, and its critics

How responsible was Mitchell for perpetuating the racism of her day?

[Note: Originally published on 2025/05/27.]

I read Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell the other month, and while I enjoyed it, I also came away confused. Not so much by the plot, which is pretty straightforward, but in what exactly I was supposed to take from it.

Like a lot of historical fiction, it tells you as much about the time it was written—the 1930s—as it does about the time it’s set—the American Civil War. But being far removed from both, reading it felt like watching history through a funhouse mirror. I had so many questions. Was Scarlett's belief that the war is pointless meant to make her sympathetic, or just cynical? What are we supposed to make of her unapologetic flair for business? Was Mitchell as racist as her characters, or was she trying, however imperfectly, to depict racism without endorsing it? Could parts of the novel even be read as anti-racist, in a weird, old-timey way? And in the 1930s, when schoolchildren were reciting the Pledge of Allegiance every morning, how did readers respond to such a sympathetic portrayal of the Confederacy?

Trying to answer these questions, I got interested not only in what Mitchell meant, but also in why Gone with the Wind struck such a chord. It’s easy to focus on the supply side—the way a story shapes culture—but cultural impact also depends on demand. A story doesn't become a juggernaut just because the author made a persuasive case. It takes off because something in the culture was already primed for it.

So I dug into the historical context and the novel's reception. Unless otherwise noted, what follows is informed by The Wrath to Come: Gone with the Wind and the Lies America Tells by Sarah Churchwell.

In the following, I'll start with some background on the 1930s, especially in Georgia and the broader South, where Gone with the Wind is set and where Mitchell was from. Then I'll look at Mitchell herself and what she thought she was doing. After that, we'll touch on the film adaptation and how the work was received. Finally, I'll circle back to the questions that first puzzled me and try to answer them.

Let's dive in.

The 1930s

To understand where Margaret Mitchell projected the 1930s back onto the 1860s, it helps to know what the world looked like as she was writing. A lot of the big debates—race, class, gender roles, national identity—resemble current preoccupations. But the stakes and tone were different, and economically, at least, we've got it much better now.

The Great Depression and the New Deal

The Great Depression, triggered by the 1929 stock market crash, sent the U.S. into a downward spiral of unemployment, poverty, and institutional breakdown. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the New Deal (1933–1938), a set of public programs, social reforms, and financial regulations meant to get the country back on its feet.

It was the first major expansion of the federal welfare state in American history, and many well-off white Americans hated it. To conservatives, it looked like a slippery slope to socialism: threatening free markets, rewarding laziness, and undermining meritocracy.

In the South, where distrust of federal power already ran deep, the New Deal was especially provocative. Many white Southerners had long viewed the Civil War not as a fight to preserve slavery, but as a struggle against centralized control, so Roosevelt's programs felt like a repeat of old grievances.

Women's suffrage

Although the Nineteenth Amendment granted women the vote in 1920, debates over women's suffrage dragged on into the 1930s, especially in the South. There, white suffragists argued that women's votes would reinforce white male political dominance. Their opponents, meanwhile, saw women's suffrage as a dangerous Yankee import and a legitimization of black suffrage under the Fifteenth Amendment. In Georgia, both camps were led by prominent members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Fascism and racism

Fascism loomed large in 1930s America. Partly because it was on the rise in Europe, but also because Nazi propaganda kept pointing to U.S. racism as a defense of Germany's treatment of Jews. Critics of Jim Crow were quick to draw the obvious parallels: lynchings, segregation, voter suppression—they looked uncomfortably similar to the things America claimed to oppose abroad. But many Americans insisted the comparison didn't hold. Nazism, they said, was an ideology; American racism, while real and regrettable, was more of a bad habit—something peripheral, not foundational. (Or just something Nazi newspapers had blown out of proportion.)

Meanwhile, Southern defenders of segregation disliked being compared to Nazis, but had no issue adopting some of the same logic. They called for boycotts of the 1936 Berlin Olympics to signal disapproval of Hitler, then fought against black voting rights at home.

The phrase 'master race' didn't start in Germany, either. It was coined by American eugenicist Madison Grant in his 1916 book The Passing of the Great Race, a bestseller that helped mainstream the idea of racial hierarchies well before Hitler made it infamous. Antisemitism was also well-established in American conservative circles. Henry Ford's The International Jew series ran in his newspapers for years, and one of the most influential public voices of the decade—Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest with a radio audience that reached 22% of Americans—spent the late '30s justifying Kristallnacht, calling Roosevelt "Rosenfeld," and arguing that the New Deal was secretly a Zionist plot, giving it the nickname "Jew Deal."

The Klan

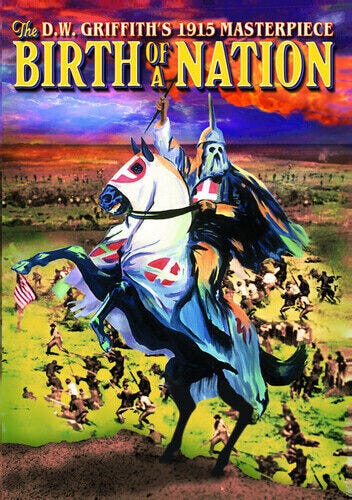

The first Ku Klux Klan formed during Reconstruction, drawing inspiration from the chivalric fantasies of Sir Walter Scott. The second Klan, revived in the 1920s, leaned into theatricality—adopting white robes, burning crosses, and cinematic flair, much of it borrowed from The Birth of a Nation (1915), which itself was based on the novels of Thomas Dixon Jr. This Klan became more popular than the first, and is more prominent in cultural memory.

In the 1930s, Americans often distinguished between the two Klans. The first was still praised in mainstream outlets as a kind of postwar neighborhood watch. A 1939 New York Times article described it as having existed for "frightening obstreperous Negroes into good behavior... applying the lash when that seemed most effective, murdering if that remedy was demanded"—often, it added, with "abundant provocation." A 1937 Chicago Tribune piece, inspired by Gone with the Wind, offered similar praise, brushing aside arson and murder as regrettable excesses.

These days we also tend to forget that the Klan wasn't the only active white supremacist terror group at the time. The Black Legion, a paramilitary group based in the Midwest, was accused of murdering up to fifty people in 1936, most of them black. Its leader plotted a coup to seize Washington, D.C., and proposed exterminating Jews by pumping poison gas into synagogues on Yom Kippur.

Even in the 1930s, the Klan was being compared to the Nazis by both its critics and admirers. One Nazi consul general in California even tried to fund a U.S. putsch by purchasing the Klan. But they declined—he wasn't offering enough money, and they didn't want foreign interference.

Criminal labor

By the late 1930s, criminal labor was under national scrutiny. Georgia's chain gang system became a scandal, thanks in part to the 1932 film I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, based on a true story of a wrongfully convicted white man who escaped, was recaptured, and re-incarcerated. In 1937, amid growing outrage, Georgia promised to abolish the practice.

Popular media

Gone with the Wind was not alone in capturing the popular imagination. The number one best selling novels of the 1930s, beyond Mitchell's, were:

Cimarron by Edna Ferber: Historical fiction about the Oklahoma Land Rush

The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck: A dramatization of Chinese village life in the early 20th century

Anthony Adverse by Hervey Allen: Historical adventure fiction about a man who, among other things, participated in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, owned a plantation in the US, and was incarcerated

Green Light by Lloyd C. Douglas: An uplifting interpersonal drama

The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: The coming-of-age story of a farm boy

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck: A realistic novel about a family's journey to California during the Great Depression

A couple other relevant works of popular fiction include:

Show Boat by Edna Ferber (1925), adapted into a film and musical about interracial love and life on the Mississippi.

It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis (1935), a dystopian novel about American fascism

More broadly, plantation fiction and minstrel imagery were cultural mainstays at the turn of the 20th century, though by the mid-1930s they seem to have faded. Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus stories and performers like Al Jolson (whose 1935 recording helped popularize the term 'moonlight and magnolias') romanticized the antebellum South. The Little Colonel novels by Annie Fellows Johnston were widely read, and the 1935 film adaptation starring Shirley Temple—featuring a dance with Bill "Bojangles" Robinson—was one of the last major films to depict the minstrel tradition.

Hollywood was also operating under the Hays Code by 1934, which, among other restrictions, banned the use of the N-word in film. But in other contexts, the term was common—including a couple of newspapers which declared "nxxxxr brown" as the color of the season1.

Who was Margaret Mitchell?

Margaret Mitchell was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1900 to a white Southern family with deep Confederate roots. Her great-grandfather, an Irish immigrant, owned a 3,000-acre plantation and held thirty-five slaves by 1854—a notable figure, given that only about a quarter of white Southerners owned slaves at all, and just ten percent of those held more than twenty. By Mitchell's lifetime, however, her family's wealth came from Atlanta real estate, as was typical for many of the city's old families.

Mitchell spent almost her entire life in Atlanta, apart from a single year at Smith College in Massachusetts, which she disliked. According to a former roommate, she idolized Robert E. Lee and reacted poorly when a black student enrolled in one of their classes. Mitchell's own explanation was that the professor showed contempt for Southern students and was hypocritical about race. Sarah Churchwell finds this defense implausible, but notes that Mitchell did harbor a deep resentment toward Northern condescension. In a letter to a friend, she wrote:

the Romans, after all, were politer than the Northern conquerors, for after they had sown Carthage with salt they never rode through it on railroad trains and made snooty remarks about the degeneracy of people who liked to live in such poor circumstances

This was part of a general belief that many of the tensions underlying the Civil War had never been resolved. When President Roosevelt endorsed a liberal Democratic senator in Georgia over a conservative one, many locals saw it as federal overreach (and compared him to Hitler, naturally). Mitchell noted that the South hadn't changed much since the Civil War, and expressed surprise that so many Northerners thought sectional divisions had been settled.

Like many elite white Southerners of her generation, Mitchell grew up steeped in the ‘Lost Cause’ narrative, which romanticized the Confederacy, downplayed slavery, and framed the South as noble but misunderstood. Her political views reflected this regional wariness of federal authority: she leaned libertarian and was described by her brother as "extremely reactionary." She was staunchly opposed to the New Deal, and kept a "Red" file on Southerners she suspected of leftist sympathies. She even considered writing an essay titled "Why the Communists Attack the South and Attempt to Inflame the Negro Press and Public Against the South."

She supported Georgia politician Herman Talmadge, a segregationist who rose to power defending Jim Crow and opposing civil rights legislation well into the 1950s. As a young journalist in 1923, Mitchell also wrote a favorable profile of Rebecca Latimer Felton—both the first woman and the last slaveholder to serve in the U.S. Senate. Felton was a prominent suffragist and an advocate of lynching, white supremacy, and the convict lease system. Much like Felton, Mitchell identified as a feminist, which was less correlated with left-wing causes than today. Her mother, Maybelle Mitchell, was a prominent Georgia suffragist, and Margaret shared many of her ideals.

Mitchell also held complicated and often contradictory views on race. At fifteen, after seeing The Birth of a Nation, she was so taken with the film that she wrote her own adaptation of another of Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novels—complete with Klan costume. Later, she praised the first Ku Klux Klan as a protector of women and children, though she opposed the second Klan of the 1920s and was disturbed by its resurgence in Atlanta, especially when black residents, including her own domestic staff, were afraid to leave their homes due to the threat of violence. Later in life, Mitchell quietly donated to Morehouse College, a historically black university, funding scholarships for black students.

Though conservative in many respects, Mitchell didn't support European fascism. She proudly noted in 1944 that Gone with the Wind had been banned in Nazi Germany. Though she heard Hitler and his inner circle had seen the film adaptation, she doubted they appreciated it: "They did not think a story or a movie which had to do with a conquered people who became free again would be a good thing to show in Germany or occupied countries."

Mitchell's intentions

Margaret Mitchell insisted Gone with the Wind was a realistic portrayal of the Southern experience during and after the Civil War. She claimed to reject the sentimental plantation fiction she'd grown up with, instead depicting a cast of modern realists—laissez-faire, self-interested characters who reflected the rise of the New South. Her Georgian characters span a range of social classes, and she prided herself on accurately capturing the white caste system, calling the book "as true as documentation and years of research could make it."2 That said, while her military history is meticulous, her political and racial portrayals were based on sources drawing from the same Lost Cause narratives she claimed to reject.

Mitchell's realism extended to linguistic and visual detail. She researched black dialect by interviewing African Americans who had been born into slavery, and insisted that her language choices were historically accurate. When a publisher urged her to soften racially charged phrases like "Mammy's ape face," "black paws," and references to "negro rule," she expressed surprise, saying she had "tried to keep out venom, bias and bitterness." She claimed, for instance, to have heard black people refer to their own hands as "paws." Still, she conceded that such phrasing might come across differently in print than in conversation.

In her correspondence, Mitchell generally used "Negroes" or "colored people" to refer to black people, both standard terms at the time, though earlier letters sometimes included "darkies." As criticism of the novel's language mounted, she doubled down on her claim that the novel's language was historically grounded, including the slurs. She expressed bewilderment that readers found the black characters offensive, insisting that Mammy, Peter, and Sam displayed more dignity and moral clarity than Scarlett. Mitchell furthermore dismissed black critics of the book as "professional Negroes" stirring up trouble, and said she was thrilled when white liberals disapproved of it.

In spite of her attempts to stay neutral, Mitchell's contempt for Northern hypocrisy comes through in the novel. In one scene, recently arrived Northern whites offend Peter, Scarlett's black domestic servant, by their insensitivity and use of slurs. The Northerners refuse to hire black staff, unlike white Southerners, who view their black servants as part of their family. Mitchell's implication seems to be that Southern racism, while overt, was less hypocritical. Historically, this framing is flawed. While the use of slurs increased during Reconstruction, there's plenty of evidence that white Southerners used slurs earlier, too. Additionally, domestic slaves were rarely as loyal as the novel implies, often the first to leave after emancipation.

Some of the novel's racial preoccupations also seem to project 1930s concerns onto the 1860s. The trope of idle freedpeople during Reconstruction, for instance, may reflect Mitchell's anxieties about federal welfare under the New Deal. Likewise, some readers found terms like "Götterdämmerung" (popularized by Wagner's 1876 opera) and "survival of the fittest" anachronistic for characters in the 1860s. Mitchell defended their use as plausible for educated Southerners, though both phrases were more common in the political discourse of her own era.

Mitchell did reveal some of her explicit intentions with her work. Scarlett O'Hara was meant as an anti-hero, and Mitchell was uneasy with how readily readers embraced her. "I have not found it wryly amusing," she wrote, "when Miss O'Hara became somewhat of a national heroine and I have thought it looked bad for the moral and mental attitude of a nation." While she admired Scarlett's courage, loyalty, and drive, Mitchell made it clear that Melanie was "really my heroine, not 'Scarlett.'" Melanie, with her quiet grace and moral strength, represents the doomed Old South. Scarlett, though less admirable, has the "gumption" to survive.

This ties in with the novel's core theme, which Mitchell helpfully made explicit:

If Gone With the Wind has a theme it is that of survival. What makes some people come through catastrophes and others, apparently just as able, strong, and brave, go under? It happens in every upheaval. Some people survive; others don't. What qualities are in those who fight their way through triumphantly that are lacking in those that go under? I only know that survivors used to call that quality 'gumption.' So I wrote about people who had gumption and people who didn't.

The film

Gone with the Wind became a runaway bestseller within weeks, and won the Pulitzer Prize the following year. The film adaptation was greenlit almost immediately after this success. By 1937, producer David O. Selznick had acquired the film rights, launching what would become one of the most ambitious and controversial Hollywood productions of the decade. Even before a script was finalized, Selznick's studio kicked off a high-profile nationwide casting campaign known as "the Search for Scarlett." Thousands of actresses were considered, and the publicity helped build anticipation for a film that hadn't yet begun production.

Visually, the film exaggerated the grandeur of the Old South—particularly the plantation Tara, which Mitchell had wanted to appear more modest—but in most other respects, it hewed closely to her text. Cuts were permitted, but additions were not. Multiple screenwriters cycled through the project, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, who found the strict adherence to the novel stifling and soon walked away.

One of the major challenges facing the filmmakers was how to handle the novel's racism. African American activists protested not just the use of the N-word, but the broader racial stereotypes embedded in the story. Mitchell and Selznick defended the language as historically accurate, but public pressure forced the studio to revise several elements of the script.

Yet public pressure wasn't the only reason that racism in the novel is toned down in the film. Selznick, the American-born son of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants, expressed private sympathy for black audiences, stating: "I feel so keenly about what is happening to the Jews of the world that I cannot help but sympathize with the Negroes in their fears about material which they regard as insulting and damaging." He also cautioned that "we have to be awfully careful that the Negroes come out decidedly on the right side of the ledger."

Although Selznick, like many Americans at the time, viewed the first Ku Klux Klan more sympathetically than the second, he briefly considered removing the Klan from the film entirely. He feared its inclusion might serve as "an unintentional advertisement for intolerant societies in these fascist-ridden times" given the Klan's resurgence in the 1930s. Ultimately, however, the Klan remained in the story.

Other changes were made to soften political messaging, though. In the novel, Scarlett's father dies after refusing to swear loyalty to the United States—a defiant act of Confederate pride. In the film, his motivation was altered to make his death more acceptable to mainstream audiences.

The reception

The novel and film adaptation of Gone with the Wind were wildly successful, both in the United States and abroad. American critics praised the novel for its vivid realism, graphic depictions of war, and complex characters—especially Scarlett, who was seen as daring, modern, and compellingly unladylike. Many readers viewed the book as a departure from nostalgic plantation fiction, applauding its frank portrayal of bodily functions, cursing, and emotional ambiguity. Scarlett's foray into business also struck a chord with women impacted by the Great Depression, many of whom had taken on similar responsibilities to support their families.

International audiences responded just as strongly. The story found large audiences in, among other places, England, France, Spain, Norway, Iceland, Poland, Japan, Vietnam, and even Nazi Germany (where it was later banned). When the film was released in 1939 soon after the outbreak of World War II, its anti-war undercurrents resonated with American isolationists, while European audiences, already under siege, saw reflections of their own wartime struggles. In London, the film played continuously at Leicester Square for four years, with audiences lining up daily despite the Blitz. By 1949, Mitchell remarked that the story's popularity had only grown across Europe: nearly every country now knew what it meant to be invaded or occupied.

The film's popularity in Nazi Germany had ideological dimensions as well. Its portrayal of the South as a culturally distinct Volk, its racial hierarchy, and its comparatively flattering depiction of slavery made it appealing to some Nazi audiences. Hitler reportedly liked the film, though some Nazi elites disapproved of the public's preference for American kitsch over German high art. Some American outlets also praised the novel for offering an "ideal plantation," in contrast to more negative portrayals such as Uncle Tom's Cabin. Even outside the South, Mitchell was commended for her depiction of black characters, including their heavily phonetic dialogue.

But not all readers were persuaded. Some critics felt Mitchell had written exactly the kind of sentimental, mythologized plantation novel she claimed to reject. F. Scott Fitzgerald placed Gone with the Wind in the same tradition as The Birth of a Nation and the work of Thomas Nelson Page—what he called the "romantic chivalry" strain of Civil War fiction. He contrasted it with less popular but more honest works by writers like Stephen Crane and Ambrose Bierce. Other critics pointed out the novel's "Fascist implications," warning that its nostalgia for hierarchy and pre-modern social order could subtly encourage readers toward authoritarian sympathies.

The story's cultural footprint was large enough to inspire satire. In early 1939, Clare Boothe wrote a comedic play, Kiss the Boys Goodbye, which parodied the "Search for Scarlett" by following a film producer hunting for an actress to play Velvet O'Toole in a Civil War romance. Boothe framed the play not just as a send-up of Hollywood, but as an allegory for American fascism. She argued that fascism in the U.S. would take a uniquely domestic form which she dubbed 'Southernism,' a soft authoritarianism that Americans failed to recognize or take seriously. Mitchell, along with other critics, dismissed the comparison as absurd.

African American audiences overwhelmingly rejected the film. Protests erupted during production and continued through its release, with demonstrators condemning it as "un-American, anti-Semitic, anti-Negro, Reactionary, Pro-Ku Klux Klan, pro-Nazi and Fascist." A journalist for the New York Age wrote that the film "openly refers to the Negroes as 'simple-minded darkies', resurrecting all the racial inferiority theories which science has discarded, and which Hitler and his fellow imperialists have picked up against Jews and other minorities."

Conclusion

When I first read Gone with the Wind, I was puzzled. Was it controversial when it came out? Did readers really sympathize with the Ku Klux Klan? Was Scarlett's girlbossing seen as transgressive, or aspirational? So I wasn't all that surprised to learn that it was in fact controversial in its time, though certainly less so than it would be today.

And yet, in spite of everything, the story holds up—well after most plantation fiction has become a historical curiosity. For all of Mitchell's politics, Gone with the Wind isn't reducible to a simple message. Mitchell favored Melanie, the novel's moral center, but also portrayed her as too gentle to endure. That tension remains one of the book's most interesting choices. Scarlett's brilliance as a character lies in her moral ambiguity—her views aren't meant to be trusted, and the novel is stronger for it.

In The Wrath to Come, Sarah Churchwell sees this moral ambiguity as a weakness. She argues that it's a failure of the novel that Scarlett, a sharp and forceful character, doesn't comment on the appalling treatment of black people happening around her. But I strongly disagree. A protagonist who perfectly mirrored the sensibilities of 21st-century white liberals would feel not only anachronistic, but insufferable. On the other hand, had Scarlett been a paragon of Southern virtue, completely persuaded of the rectitude of the Confederate cause, the story would have been unreadable in a different way. Mitchell struck an impressive balance: Scarlett's disdain for the war is both sympathetic and rooted in her lack of moral core. I wasn't surprised to learn Mitchell was a libertarian, but I wouldn't have been shocked if someone had told me she was pro-labor union either—Scarlett's labor practices, after all, are depicted as morally bankrupt.

Still, fiction is more than authorial intent. Gone with the Wind didn't just reflect its time—it helped shape it. It's implausible that a book this popular wouldn't have influenced how readers, both in the U.S. and abroad, thought about the Civil War and its aftermath. And yet measuring that influence is slippery. As with all cultural products, it's hard to separate the role of supply and demand—do popular stories shape culture (supply), or does culture decide what stories get popular (demand)?

While both forces are always at work, I think Churchwell overrates the power of the supply side. Gone with the Wind could only become as influential as it did because it struck a chord with its audience. If it had been published today, it wouldn't have taken off—had it gone to print at all. Likewise, many books that are critically celebrated today wouldn't have stood a chance in the 1930s. There were things you couldn't get away with then just as there are things you can't get away with now.

Churchwell acknowledges that fiction about the horrors of slavery often fell flat in the 1930s. But she seems too outraged to ever compromise, an ultimately ineffectual attitude. The truth is, demand matters. The culture has to want what a story is offering. That's why I'm skeptical that a version of Gone with the Wind that appealed to a broad audience while offering a sharper critique of slavery and the Confederacy could have succeeded in that moment. It might have been praised in niche circles, but I doubt it would have had mass appeal or enduring influence. Beyond that, overly didactic fiction is often terrible.

And while a book with a more positive social impact may have improved things at the time, today, I'm glad Gone with the Wind exists as-is. The novel provides a rare window into how white Southerners saw themselves—or wanted to be seen—in both the 1860s and the 1930s. Mitchell's portrayal of white characters justifying slavery doesn't feel like a modern author trying to inhabit the mindset of their ancestors. It feels like someone writing from within the logic of that world. And because of that, the story feels plausible.

Of course, just because a book needs cultural traction to become influential doesn't mean supply-side explanations are always wrong. Some stories really do shift public imagination. Churchwell comments that KKK vigilantes after The Birth of a Nation were doing more than just LARPing. But to the contrary, I think the conclusion is that it was a LARP—but that LARPing is extremely powerful. So perhaps there was room in the 1930s for a novel or film that would make people LARP something better.

But I'd wager there wasn't. It's frankly a little unbelievable that Mitchell expressed such surprise that readers glommed onto glamorous Scarlett instead of mousy Melanie—glamour is a real strength of the novel. And glamour is never fully honest.

To be specific, it was in the 23/03/1937 edition of the Camden County Courier-Post, and the 18/07/1937 edition of the Star Press from Muncie, IN.

One thing Mitchell didn't research, however, was the Ku Klux Klan, stating that "As I had not written anything about the Klan which is not common knowledge to every Southerner, I had done no research upon it."